As physical doors close, new digital doors swing open

May 21, 2020 by Jenny Child, Rod Farmer, Thomas Rüdiger Smith, and Joseph Tesvic

In the first article in McKinsey’s series The story of the Australian consumer, we look at Australian consumer sentiment in response to COVID-19 and ask whether these responses are aligned with the health and economic realities of the country’s pandemic experience to date. Article two combines ethnographic enquiries with our consumer-survey insights to paint a more vivid picture of the changes underway in Australian households. We see shifts in spending, changes in consumer preferences, forced and accelerated adoption of digital technologies, and rapidly increasing consumer expectations of and adaptions to new household dynamics, including the mental strain of isolation.

In this piece, we’re taking a deeper look at how the Australian lockdown experience has created a new set of digital users and at what businesses can do to emerge stronger after the COVID-19 crisis. While the future is still in flux and new habits haven’t yet been solidified, our initial data on consumer uptake of digital technologies, matched with historical parallels, point to significant changes for the digital sector.

Was that your mum I saw on TikTok?

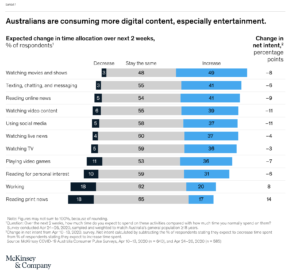

Australians’ use of many things digital has traditionally lagged behind that of most Indo-Pacific peers, but people in this country are now seeing that there is no virtue like necessity. McKinsey’s Consumer Insights Pulse Survey shows Australians consuming more digital media, doing more online shopping, and using more online services than ever before (Exhibit 1). Clear shifts are observable in the age segments that have been hardest to convert.

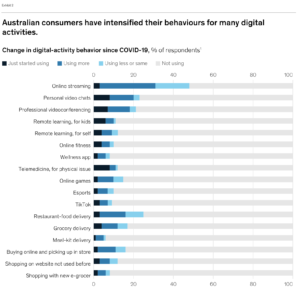

The national increase in digital-media consumption is well understood; Netflix reduced streaming rates, and NBN released free bandwidth to meet demand.1 But the change extends well beyond extra time on the couch. The restrictions of lockdown compelled a whole segment of Australians to shop online for the very first time. They have also forced consumers to try out new forms of digital interactions, like video-enabled “hangs” with friends, online fitness, and telemedicine (Exhibit 2).

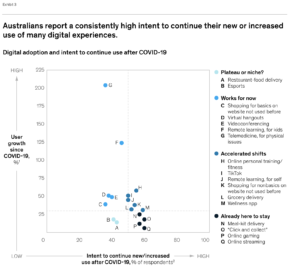

Satisfaction levels with digital usage and “intent to continue to use” are also quite high (Exhibit 3). For example, of the consumers doing fitness activity online, 40 percent are satisfied with the experience, and 55 percent state their intent to continue. Even e-groceries—a sector that has experienced significant logistical challenges, extended delivery windows, and sporadic availability of product—has left more than 60 percent of consumers reporting that they are “very satisfied” with the experience. There is a similar outcome with the uptick in telemedicine, which has been tried by 10 percent of consumers, many for the first time: 60 percent of those users are “very satisfied.” High satisfaction levels for activities whose online efficacy has historically received a fair amount of scepticism are a good sign of postlockdown “stickiness.”

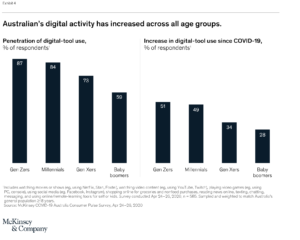

And this digital uptick is far from limited to Gen Z and the millennials. Seventy-five percent of Gen Xers have shopped online for nonfood products in the past two weeks, and of those more than 40 percent are shopping more in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The same holds true for digital tools, such as media content and social media: 34 percent of Gen Xers and 28 percent of baby boomers say they have increased their usage since the lockdown started.

These examples highlight the Australian consumer’s willingness to experiment with and adapt to new activities in digital formats. This opens the door to a long-debated question about digital supply and demand and why the penetration rate of online commerce is lower in Australia than it is in the United States and Europe—about 10.8 percent, 15.2 percent, and 18.3 percent, respectively.2 In the past, many argued that the Australian consumer just really values the brick-and-mortar experience and doesn’t want to let it go. Privacy is also a factor: before the pandemic, about 30 percent of Australians cited concerns about privacy or fairness of price when shopping online, according to recent McKinsey proprietary research into online shopping in Australia and its implications for retailers.

But now, after so many new users have been trying e-commerce, liking it, and reporting that they will continue to use it, has momentum fundamentally shifted? If given the choice—physical stores or online—with equal quality, will channel usage and demand shift to digital at a faster rate than it did before the COVID-19 pandemic (Exhibit 4)?

And what will this mean for the large and sprawling brick-and-mortar footprints of many Australian retailers? Last year, the evidence signalled that selling space over the coming five years would decline by more than 10 percent across retail industries. With this uptick in digital, and with discretionary expenditures falling, how quickly will offline retailing need to shrink to keep pace?

One thing that is certain is that Australian businesses have a lot of big moves to consider, so it’s worth exploring what it would take for them to go on an accelerated digital journey.

Investing big in the digital journey

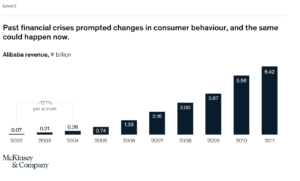

For those wondering if these changes in consumer behaviour will be the impetus for change, a look back to the emergence of digital services, and consumers, in the wake of the SARS3 outbreak in China and South East Asian markets in 2003 suggests that the potential is certainly there (Exhibit 5).

In 2003, Jingdong (now known as JD.com) was a small chain of 12 brick-and-mortar electronics shops in Beijing. In response to SARS, the company rapidly reversed course on storefront retailing and instead focused on building a fulfilment infrastructure and then leveraging it through increased range. Alibaba was a four-year-old B2B e-commerce company in 2003, with a business model focused on matching US procurement teams with Chinese suppliers. When nations around the world issued travel warnings on China, Alibaba saw a way to connect small and midsize Chinese companies with the world. Wholesale buyers embraced this online gateway to source Chinese goods. In turn, Chinese suppliers invested more in online marketing on Alibaba’s platform, rapidly creating a self-perpetuating critical mass.4

A critical lesson, though, was that this growth was not achieved without substantial infrastructure. The Chinese government had established an enabling infrastructure for the B2B industry, linking a policy and infrastructure e-governance platform at the central level with local governments to ensure the accurate and timely flow of information and resources to enterprises. This infrastructure helped more enterprises become internet enabled and sped the expansion of e-business through a suite of accessory policies on online payments, credit, safety certifications, and logistics.

As Australia’s businesses eye the rapid adaption consumers have made to all manner of digital experiences (shopping, social, business, health)—and as Australia’s governments move their focus from stemming the bleeding to practical recovery—there is a discussion to be had about what policy and regulatory support is needed to enable a more digital Australia. What are the key issues that Australia’s businesses (and regulators) need to address to cope logistically and deliver on both the first and the last mile?

This conversation is critical. The potential for widespread demand that can fuel a new digitally enabled economy in Australia is real. And a more digitally enabled economy is an aspiration worth embracing, not just economically, but also civically. Important services can be provided at lower cost (for instance, routine health checks). There can be more equity in access to goods and services across geographies. Consumers get more price transparency and more choice (such as “the endless aisle”). Greater personalisation, data analytics, and machine learning can make services from both businesses and government more agile and adaptable.

And while Australia’s big legacy brick-and-mortar players have historically not chosen to shift their resources and capital expenditures from offline to online in a significant way, it’s important to remember that the stores we left will not be the stores to which we will return. COVID-19–related regulations and restrictions will disrupt in-store experiences and probably greatly diminish the “touch and feel” benefit of shopping in person for the foreseeable future. Some stores and cafés will go out of business, and shopping districts could feel less “buzzy.” Ongoing physical distancing may make the in-store experience less efficient and convenient.

Finally, even as stores reopen, Australia’s consumers will also have changed. Retail environments and experiences have been built over generations to encourage consumers to forget time or why they came, to stay longer, to bring friends, to see the experience as a product in itself. This relies on the expectation that consumers will be leisurely, distractible, relaxed, playful, and communal—which may all easily be overridden by a more focused, task-oriented, and cautious shopper.

Match all of this with that uptick in familiarity with many things digital during the lockdown—as well as the relatively high satisfaction levels—and the long-held native advantage of Australia’s brick-and-mortar stores may be diminished.

Emerging stronger

The situation at hand evokes five key questions:

- Are established e-retailers (such as The Iconic) fundamentally advantaged to go after growth with this new digital uptake? Will producers of fast-moving consumer goods and of consumer packaged goods go after more direct-to-consumer pathways? How much market share is at stake by category?

- Will any local or international retailers step up to fully invest in new first-mile capabilities that offer consumers an experience better than or rivalling the in-store experience?

- Will native brick-and-mortar players be able to build efficient online supply chains to match online and offline margins?

- Will there be much-needed innovation in delivery (such as Uber, crowdsourcing, and new tech) or in players to close the last-mile gap?

- Will governments strategically support and encourage investment in Australia’s digital infrastructure and economy?

There is a big chance that the post-COVID-19 “resilients”—businesses that will drive a disproportionate amount of market growth after the reopening, as happened after the global financial crisis—will be the innovators, the disruptors, the ones that take bold action to embrace Australian consumers where they are.

The offline and online battle won’t have a binary outcome. The players that can use the best of both channels to deliver a new, inspired, and meaningful experience will be the ones that win the hearts (and pocketbooks) of the post-COVID-19 consumer.

About the author(s)

Jenny Childis a partner in McKinsey’s Sydney office, where Rod Farmeris a senior expert, Thomas Rüdiger Smith is an associate partner, and Joseph Tesvic is a senior partner.

The authors wish to thank Karthikeyan Swaminathan and Daniel Zipser for their contributions to this article.

Find the original article here.